George and Uche belong to the same generation. Born in 1972 and 1973 respectively, they are good friends and they have more than a few things in common. Now, they have one more: the last two additions to the growing contemporary art collection at Lagos Business School are works produced and placed “in situ” by them. Both pieces, Peters’ “Free yourself” and Edozie’s “LBS” can be seen, suspended from the ceiling, in public areas of the LBS buildings at Ajah, Lagos.

In 2009 I helped putting together an exhibition at Omenka Gallery titled: Nigerian abstract painting now. George Edozie and Uche Peters (at that time his name was still Uche Igwe) participated in it. Since then, Uche has produced only a few works, mainly using galvanized steel wire, while George has been a prolific artist, increasingly incorporating textiles into his works.

Uche is an unusual artist. He did not study art; he does not earn a living through art, he is not a member of any professional art body, but there is no doubt about his being an artist. His works prove it, even if some art bureaucrats might disagree, adducing that he is not one, because he is not “registered” somewhere.

He has experimented with wire sculptures for the last five years. He “crochets” and twists the thin galvanized steel wire into two-dimensional “fabrics” that he then uses to create three-dimensional works. Since he runs a catering business that takes most of his time, producing one of these sculptures requires of him months of work.

Uche’s works have little to do with the ubiquitous wire sculptures sold at tourist markets all over southern Africa. He is not interested in producing tourist crafts, but he is an excellent craftsman. As he does not use soldering for his work, the cold joining method forces him to “bound” the wires around themselves. This is heavy, physical work, but the end result is excellent. The wires are beautifully intertwined creating works of delicate complexity.

But there is much more than skill and hard work. Each of his pieces explores issues, questions assumptions, and engages the viewer on a discourse. Uche has a great ability to “embody”, to materialize ideas into physical art works. In this case, the underlying narrative is about freedom and about the sad capacity we human beings have of creating self-imposed boundaries made of fears. The human body enclosed in the wire fish has his/her eyes bound. He can’t see that the tools to free himself are close at hand, because, also within the belly of the fish, there is a mallet, a saw, a pair of pliers, a phone and a knife. If the hopeless figure were to remove the cloth from his eyes, he would be able to use these tools to free himself… This is a powerful metaphor, delicately crafted into an arresting piece.

The other new artwork at LBS is also a suspended “sculpture”. Produced and mounted in-situ by George Edozie, in the main foyer of the School, this is a suitable piece for the large, high-ceilinged, bright space.

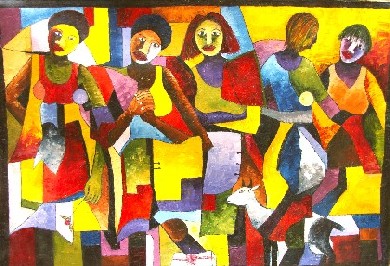

George trained as a painter and has always worked as a painter. It shows in the way he has treated this tri-dimensional piece. In his paintings on canvas he normally applies raw colours on the cloth and works them with the knife. The play between surface, colour and texture is central to his work. In the LBS letters, it is as if the “canvas” had been wrapped around the steel frame that supports the letters. His work is two-dimensional even when the surface is not. In this sense, his work is “superficial”, and with this word I do not suggest that it lacks depth. It is simply that he works on the surface of a tri-dimensional object, as if he had done it first on two dimensions and then enveloped the letters, like a flat cloth covering a body and taking its shape. He is still a painter that has “painted” these letters not with brushstrokes but with shreds of cloth… This piece is not “moulded”, this is a piece “covered”. It shows that this is not the work of a sculptor, but the work of a painter, and, again, I say it not pejoratively.

In this work George decided to arrange the cloths in vertical shreds. This is a subtle and successful choice. From the distance at which the piece is seen, the cloth is not “read” as cloth, but as an aggregation of multicoloured, vertical “scales”.

The central place given to “surface” is clear, but the volumetric, spatial quality of the work can’t be dismissed. The “body” is not fully hidden under the “cloth” that covers it. The sheer size of the letters (more than 2.00 meters high) plus the tension created by the dialectic between large volume and “floating” suspension are also at the centre of the success of this work.

Lagos Business School has taken a risk with these two artworks. Perhaps they will not be appreciated by everybody; the detractors will continue asking the old question: but, is this art? I do not know whether it is or it not, but I think LBS has done the right thing risking a little and going beyond the conventional. I hope they continue inviting many other artists to surprise, inspire and challenge us with their works. George Edozie and Uche Peters have done so quite creditably. Congratulations to them (and to LBS).