Ben Osaghae is a remarkably consistent artist. Since he finished his studies in 1986 he has been working quietly and unassumingly, but he has never lacked strength in his formal approach to painting and in his relentless commentaries on social issues.

I started looking at his latest exhibition at Terrakulture (March 6 -11) with a sense of “deja vu“. I felt like saying “Ben, I have seen this before…” but it did not take long to realize that this would have been a simplistic comment. For sure there is continuity in Ben Osaghae’s work. For years we have seen him working on a well defined palette, his black lines marking the contours of the figures are always there, the way of applying the pigments remains largely unchanged, the size of the canvases and the compositional strategy with his “floating figures” are the ones we know. Nevertheless, Ben Osaghae keeps renewing himself. Each new work is a new story that “needs to be said”. and, he is good at telling is “stories”.

At a time when so many “fireworks”, that glitter for an instant and then die, are being lunched by all types of artists, Ben Osaghae offers “serious works”: well drafted, well composed, well executed, well inserted into a socio-political context. Unfortunately, he is little known outside a relatively small circle, but as the years pass his artistic stature grows. This exhibition might not be a milestone, but it is definitely a stone that strengthens his position at the forefront of contemporary Nigerian art.

I copy below what Kunle Filani wrote as introduction to the brochure of the exhibition.

I hope you can wade through his prose, dense and over-rich in adjectives.

He points out at a few interesting features of Ben’s works.

RADlCALlSlNG THE CANVAS: BEN OSAGHAE’S FORM AND CONTENT AS INTERLOCKING SYMBOLS FOR SOCIAL RE-ENGINEERING

Ben Osaghae paints from memory. He snapshots with his mind’s eyes and processes mental negative from the depth of his intellectual pool. For him, art is a means of accessing and assessing realities; it is a window for increased social awareness and a means of evaluating the human condition.

In order to effectively understand Ben Osaghae’s artistic (r)evolution it is pertinent to key into the depth of his intellect which hallmarks his ingenuity. A curious perusal of the inner crevices of his mind reveals peculiar creative nuances attributable only to introspective thinkers. He is sagacious in content analysis and schematic in formal presentation. Ben derives creative energy from being a perfect draughtsman. He can quickly absorb spectacular details from life experiences and process perceived images in schematized formats. He often times depicts socio-political innuendoes in surprisingly innocuous manner. He encapsulates his message in formal witticism, thereby luring the viewers into poetic conversation. Ben does not engage in pictorial sophistry to obscure the truth; he seems to prefer fact far above fancy.

Curiosity grips me each time I see Ben Osaghae’s painting. There is an irresistible presence; somewhat futuristic and adumbrated. I find it difficult t o decipher the sense of premonition that accompanies the picture plane. Beyond the intellectual directness of the form and content lies a vertical sensibility connecting the physical with the spiritual; a commune of the human and the divine. Ben multiplies visual illusions by creatively managing spatial platforms. He uses volume to create avoid and vice and versa thereby alluding to ambivalent spectacle.

In comparative creative classification, Ben Osaghae ought to be a poet, a poet who abhors canons. His grammar would have been constructed in staccato. He would have knitted his words into meaningful lines with imaginary blinders. His space would be participatory, and the reader would have filled it with speculative imagery. His paintings are his poetry.

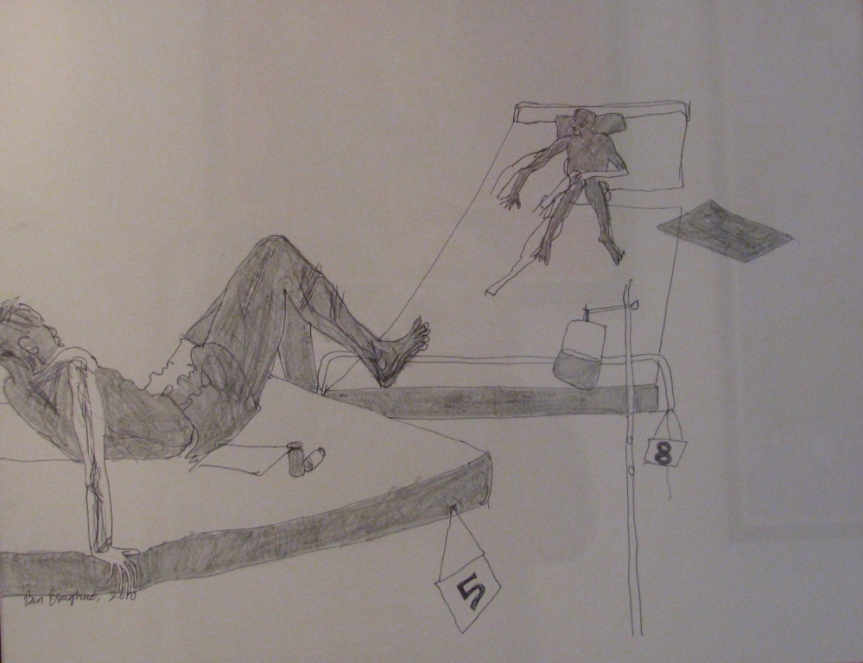

Ben Osaghae paints by drawing with brushes. This makes line his most significant element of design. Line defines forms, creates shapes and suggests space in his pictorial frame. He uses lines to interlock the fragments of images that punctuate his canvases. A good draughtsman, he creates a symbiotic balance between fine, thin and thick strokes. He also creates subjective connection with imaginary lines in-between the images. He lends solidity albeit flat and graphical to the forms by filling the space with colours achieved with rapid brush strokes. The brush strokes are sometimes lazy scribbles that mirror Joan Miro’s Kinetic lines.

Ben Osaghae’s figures and objects are mobile in pace and in space. He situates his human figures in dramatic gestures His drawing ability manifests in his skillful foreshortening poses. He allows his images to levitate in space without losing sight of relative spatial perspective. The images are comical or melancholic depending on the intended message of each painting. He interestingly crops off upper parts of the limbs of figures depicted at the edges of the picture plane. This is done with so much articulation that, rather than give the impression of amputation, participatory visual illusion of wholeness is created.

In the hands of Ben Osaghae colours become instrument of social commentary both in application and appearance. He liquefies oil colours with attendant circumstantial drippings. Transparency that is peculiar to water colour is creatively achieved with over lapping variety of hues. He characterizes his figures with symbolic colours and dramatic movements. Whereas Ben was a prominent member of the Auchi School where painters romanticized their canvases with evocative sweetness, he no longer engages in boisterous attractiveness. He does not apply oil with definite hard-edge impasto anymore he now lays thin coats of fluid hues to create silhouetted images against the vast compositional space. Ben Osaghae colours are now flat, fluid and almost frigid. He nevertheless experiment with the application of variety of hues derived from primary colours.

Ben Osaghae’s compositional arrangement is largely asymmetrical. His paintings are often off-center focused. He seems to intentionally distract from the centre thereby creating an illusion of mobility. He stabilizes the pictures visually by the introduction of amorphous objects and cropped limbs creeping in from the edges of the canvases. He achieves a peculiar delicate balance between the volume and the void thereby creating levitational perspective. He flouts gravitational rules and subjects objects to sensational float.

There is a plausible linkage between Ben’s experience in the desert region of Northern Nigeria and his emotion for atmospheric space. For a few years after graduation he lived in Sokoto, an arid Nigerian city and the seat of the caliphate grandeur. Images shimmer in the hot hazy and dusty harmattan seasons and Figures levitate in the glitter of mirage. Illusion of space is exaggerated and spatial relations of volume and void becomes specious. As a painter of distilled memories, Ben Osaghae seems to have defined his compositional arrangement and stylistic organization from the Sokoto experience. His forms, though naturalistic are no longer sincere to reality -they shimmer in relative stylization. The objects are no longer fidel to spatial perspective; rather they are creative motifs fulfilling design obligations.

In Ben’s paintings, space is glorified. One cannot help comparing the pictures to possible snapshots of future human activities in the moon. For Ben Osaghae, space defines the foreground, the background and even sometimes constitutes the objects in the composition. With the ambivalent use of space as volume and void, he creates in his works an ambience of schematic abstractions, especially when viewed from the perceptive sense. The contextual appreciation of his paintings is located in two visual polarities- the narrative and abstract structures.

To appropriate an understanding of Osaghae’s contextual disposition one must scrutinize beyond the formal rendition and connect with the meanings that the paintings generate. Ben maintains a measured balance between reality and illusion. He develops the intellectual offerings in tandem with the emotional outpourings, thereby lending robust aesthetic credence to social understanding. It is significant to contextually associate Osaghale’s dynamic formal intellectualism to the mental alertness displayed in his writings. For an artist who trained in a skill –oriented polytechnic, it is remarkable how well he developed himself intellectually. He is one of the few artists who can articulate their thoughts in theoretical presentation.

For Ben, art is a mental construct; he defines the creative process as a challenge that brings release. Painting is not merely fulfilling the urge to create. It is a means to liberate the self from the shackles of pent-up memories – human frailities, innermost passion, childhood imagination, socio-political flashbacks, humiliating, economic conditions, spiritual contradictions and the binary of polarities. Ben Osaghae romanticizes the grim realities of the Nigerian society and sometimes paints a series of the same theme. He employs sequential narratives as a means of expression. He confessed to constant soliloquy while unraveling mental challenges that come with form and content as interlocking symbols for social re-engineering. The implosion of contesting and contextual ideas as subject matter, and the manner in which they should be formally arranged generates robust aesthetic experience for him.

I have once remarked that Ben Osaghae “satirises the basic conditions of human life with cartoonist expertise” For Ben like the cartoonist, message is very significant; yet the artist in him must appeal to the viewers’ aesthetic response the trough a skillful appropriation of formal elements and principles of design. The titles of his works are seemingly innocent, yet when subjected to deeper reflections, they become venom for social commentary. A few examples of his serial themes shrouded in binary allusions should suffice.

The Prison series come with specific titles such as Prison Food, Cell Number 10, Lock and key, The Prison Choir etc. They are visually and thematically unified by the prominent presence of barricading grids locking up deprived figures within and even without the compositional balance. The satirical pun in Ben Osaghae is at play in the Prison Series. He seems to be saying that “we are all prisoners” in this world; especially in the Nigerian society. He uses motifs of incarceration and dehumanization to drive home the agonizing conditions of Nigerian prisoners. Predominant among the symbolic forms are locks and keys, bars of iron, shackles of chains food containers; and suggestive cropped limbs. The horizontal and the vertical criss-crossing bars of barricading motifs predicate human and divine justice, not only for the criminals, but also for leaders who are responsible for social aberrations in Nigeria. In spite of the physical space of freedom that dominates Nigerian societies we are yet slaves and prisoners in our homes, offices, public arenas and even spiritual graves due to social and economic insecurity fostered on us by inept, wicked and corrupt leaders and officials in government.

In Ben Osaghae’s Spiritual series, there are also specific titles such as Prayer Warriors1 and 2, Prosperity Envelopes etc. He equally unifies the forms and motifs by depicting worshipper in supplicating gestures and punctuating the pictorial surfaces with instruments of votive offerings such as tithe and offering envelopes, crosses, candles and musical instruments. He explores the mundane within the context of the supernatural by revealing the quest for riches and miracles in a society where poverty drives many to pastoral pastures. Ben seems to highlight the unwholesome emphasis on financial prosperity in the church at the expense of salvation of the soul, while also expatiating on the futility of faith without work as espoused by the patriarchal Apostle Paul.

There are other expression like Vox Pop series consisting titles such as BRT Bus, Pay Toilet, Service Delivery, Old Girls and Room 33. The themes are mundane but critical to the understanding of the social conditions of Nigerians. He exploits dramatic and schematic forms and composes in unequal spatial relations. The background is spacious and rendered flat using one predominant colour. Images are gingerly scrawled on the flat surfaces of the picture frame without special recourse to linear perspective. A sense of disorientation is usually created, thereby lending form to the unsavoury social circumstances in which the masses find themselves. The series are exquisite excoriation of government’s neglect of public service and an indictment on visionless leadership at all strata of governance.

Ben Osaghae has matured over the years especially in the matching of creative images with thematic imagery. He certainly has dematerialized human figures in pictorial arrangement relies heavily on motifs and forms for compositional balance. For him, the concept of “finishing” is quite elastic. He pushes the limits of vision with austere visuals and he gives room for the viewers’ imaginary participation in the seemingly unfinished paintings.

Should Ben be careful with over-intellectualizing art at the expense of craft? The answer levitates, like his images, in the womb of space.

Kunle Filani (MFA, Ph.D)

Provost

Federal College of Education, Abeokuta, Nigeria