I have put together a list of twenty five Nigerian artists born around independence year and I am surprised by the depth and breath of a group born in such a short period of time. For want of a better name, I call them the “independence generation”. They already play a central role in the current art scene in Nigeria and their relevance and influence continue growing. Here is the list:

1958: Mike Omoighe, Abiodun Olaku,

1959: Tola Wewe, Jerry Buhari, Olu Amoda, K. Adeyemi, E. Ekpeni

1960: Jari Jacob, Ndidi Dike, Chinwe Uwatse, E. Debebs, Dilomprizulike, E. Ikoro

1961: Duke Asidere, Sam Ovraiti, Edosa Oguigo, Tonie Okpe, E. Ekwere

1962: Ben Osaghae

1963: Olu Ajayi, Alex Nwokolo, Lara Ige-Jacks, Victor Ekpuk, Ini Brown, Pita Ohewerei

Surely, I have missed important names, but those in this list represent a broad spectrum of contemporary art in Nigeria. They studied first at Zaria, Nsukka, Ife, Auchi or Lagos; later, some “regrouped” under different banners; others remained on their own, fiercely independent. A good number of them became teachers. Most, ended up in Lagos; a few are in the “Diaspora”.

On Saturday, May 10 there will be at Pan-African University (V.I. Campus) a viewing of some recent works by a member of this “independence generation”: Duke Asidere. He is not the most vocal, the most prolific, the most daring, the most articulate, the best known in this group, but there is great consistency and quality in his works. There are not many chance to see his works, so this is a welcomed opportunity.

He finished his Masters in Fine Arts in Zaria in 1990 and moved to Auchi, were he was a lecturer from 1990 to 1995. The fact that one of the subjects he taught there was Art History shows in his works and in his conversation. I asked him once about the artists that had a greater influence on him. He mentioned Odutokun, Ikoro, Osaghae, but he also mentioned with familiarity the early fauvists and expressionists. With simplicity, he told me as well how in the 90’s he saw for the first time a few reproductions of paintings by the German-American expressionist Hans Hofmann and how this fortuitous discovery touched and affected him in a way that no other painter did. From then on, he faced an empty canvas in a different way. Hofmann was an important artist, but above all he was an art educator. Despite the obvious difficulties, he succeeded in combining both tasks: “Being an artist and being a teacher are two conflicting things. When I paint, I improvise… I deny theory and method and rely only on empathy and feeling… In teaching, it is just the opposite, I must account for every line, shape and color. One is forced to explain the inexplicable.”

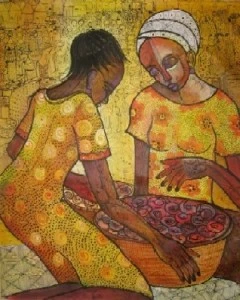

In seems, the five years Asidere spent teaching in Auchi convinced him that the conflict was irresoluble and he decided to move into full time painting. This was 13 years ago and since then Asidere has worked steadily, if not prolifically. There is one quality that separates him from most of his contemporaries: his cool self-control, the understated gesture that does not say more than necessary and does so with the most simple means. His large format oils on canvas rarely “shout” at the viewer. The serenity of his character is reflected in the calm assurance of his works. It becomes inevitable to compare him with Ben Osaghae. They are contemporaries, they were lecturers at Auchi at the same time, they share a basic approach to painting and they have not very dissimilar views on the their identities as African painters in a global art world. They even share important formal traits: the position of human figures on neutral backgrounds, the treatment of colour and texture, the use of lines to define boundaries. But a painting by Asidere is immediately recognizable from one by Osaghae. Asidere is stronger with colours, Osaghae with lines. Most of Asidere’s works have a tranquil lyricism infrequent in the strong works of Osaghae.

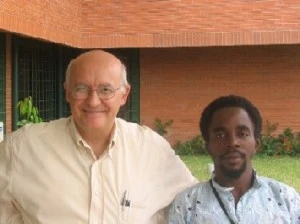

For those of us living in the extreme east of the city going to Asidere’s studio in Egbeda, north west of Lagos is like traveling to a different town; mile after mile after mile of an interminable maze of streets, roads, detours, and lanes. Most times, visiting the studio of an artist is a rewarding experience. I have visited Duke’s only once and I am glad I did. He is one of those artist you want to know more about and come back to see his works. Thanks to Pan-African University for giving us the opportunity of doing it again.