When a few days ago I went to the opening of Moyo Okediji and Tola Wewe’s exhibition “The return of our mother” little did I know that behind the polite pleasantries of the opening speeches there were substantial art historical issues coming to the fore.

Neither Moyo nor Tola referred much to the origins of the Ona movement. Nevertheless, on Friday July 29, 2011 Moyo Okediji published in several Lagos newspapers an important article titled: Beyond Dispute: Origins and Travail of the Ona Art Movement . In it, he gives a brief, but clear, account of the beginnings of the Ona Movement.

This is very good news for those of us concerned about the dearth of rigorous documentation on the development of modern Nigerian Art. I hope Moyo, and the other members of Ona, can expand this summary story and provide a more detailed and comprehensive account of the movement.

This is the “hottest topic” in Lagos art circles, so, in case you missed it, I copy the links to the article as it appeared in The Guardian, 234 Next, and The Nation.

I wonder what Moyo thinks about the way the website of the Federal Ministry of Information and Communications refers to Ona.

Category: Readings

Another gaze into contemporary art in Nigeria

In 2005 Simon Njami, the Cameroonian art critic and co-founder of “Revue noire” wrote and important article titled “Another Gaze” on contemporary African art in the context of a globalized world. Since then the discourse has moved on substantially, but I think it is still worth reading.

Njami proposes a good number of suggestive ideas, but there are three that I found particularly adequate for our current situation in Nigeria.

1. First, he identifies the two main directions taken by contemporary art from Africa: the ‘internationalists’, who reject every form of triumphal exoticism and Africanism…and the ‘authentic’, the heritage of Les Magiciens de la Terre, most prominently represented by the collection of John Pigozzi.

2. Second, he emphasizes the need to “return to the artist”: “The lesson we’ve learned from the past 15 years and that will serve as our guiding thread, is that we must look at every contemporary African artist according to his or her own inspiration, regardless of any other context. Here, the context is understood as personal experience and shifts it away from any form of territoriality.”… “It is necessary to understand that it is no longer thinkable to accept the dictatorship of the market that not only sets up the prices, but also influences fashions in art and its inspiration. We must return to the artist, talk about the artist, analyse the work with all the tools at our disposal – none should be left out.”

3. Third, we insists on the need to promote a curatorial approach, “which substitutes a nuanced, individualised treatment of contemporary African art for an overwhelmingly territorial one”.

I copy below some of the most important paragraphs. The whole article is available at http://www.metamute.org/en/Another-Gaze

ANOTHER GAZE

By Simon Njami

In the past 15 years, contemporary African art has found its audience – a public. It is now usual to come across African artists taking part in international biennial exhibitions or being shown in European, American and Japanese galleries. This development was confirmed by the nomination of the Nigerian Okwui Enwezor as director of the last Documenta in Kassel. African art has become a constituent part of the international contemporary art discourse. The theoretical basis has been supplied by publications such as Revue Noire, followed by Atlantica, NKA and Coartnews. They form a pool of information from which all sides draw raw material for a debate that finds its roots in the 1980s. An important role was also played by a series of group exhibitions, which contributed to the increasing recognition of African art. Yet, in the global village that has been forced upon us by the new world economic order as inevitable and necessary, the role of Africa and its artists still needs to be defined. One of the paradoxes that has accompanied the evolution of this discourse is that it has been forged, to a great extent, outside of the African continent. The rare events staged on African soil are the Bamako and the Dakar biennials, the chaotic biennial in Cairo and the ephemeral biennial of Johannesburg. Questions concerning the recognition of African art production therefore remain: what gets included, according to what criteria and what strategies?

The question that is being raised here is that of the inadequacy of our references. Postmodernism and its analyses point us to a monolithic view of the world, excluding everything that does not seem to fit in to its model of accepted discourse.

If the last 15 years prepared the ground for integration rather confusingly, what path are we now to follow in this stuttering century, and what will be the situation of the continent and its artists? Every attempt to answer this question must first return to the landmark events that influenced our understanding of African art within and outside of the continent. The simplest way to achieve this must be an overview of various exhibitions and an attempt to reintegrate them into the context from which they emerged. Every exhibition triggered off a debate and made a position felt. Looking at those years one would have thought that, in the last part of the 20th century, the Manichean temptation of radicalism could have been avoided. But truths clashed and came face to face amidst a cacophony that is blatantly oblivious to history and its lessons. Thus the field of contemporary African art gradually transformed itself into a vast, economic and theoretical battlefield, one that forced the various actors into defending sometimes restrictively narrow definitions.

The discussion was even more passionate since when it comes to African art there is a tendency to reduce it almost completely to the conditions of its making; every attempt to understand the shifting truth as an illusion of reality projects a certain definition of Africa and Africans. Art historians, gradually replacing the ethnologists in this field, have tried to reach a definition of African specificity, while placing the continent on the wider map of international art. Such deliberations necessarily throw up the complex question of the parameters of such a definition. What do we have in mind, or rather, should we have in mind, as we tackle the problem of contemporary African art?

The ‘80s were harbingers of what the ‘90s were to confirm: the definition of the world is no longer the exclusive prerogative of the rich countries. First theories of globalization sprang up – not dissimilar to the theories of universalism of the 18th century. The need to initiate a discussion on contemporary art in Africa became ever more evident. Ethnographic contextualisation has gradually been replaced by decontextualisation; one misunderstanding expected to chase away the other. The flaw in the idea of a global village, as imagined by some, is its inability to avoid repeating the old instincts of appropriation.

Even though Suzan Vogel’s 1991 exhibition Africa Explores the 20th Century, at the Center for African Art in New York, opened two years after Les Magiciens de la Terre, it marked the swan song of the ethnological era, representing as it did the core of the praxis that was then en vogue within the ethnographic milieu. The title indicates that its aim was to show a century of African art, but according to which criteria? Suzan Vogel solved the problem by avoiding making any choices. She renounced taking the risks that she was perhaps unable to take. The exhibition therefore portrayed Africa as a complex and overcrowded continent. Africa Explores was not so much an art exhibition as an ethnological representation of context at the expense of aesthetics. Just as colonial exhibitions had done in the past, it set out its stall, showing everything it possibly could. It was up to the audience to make its own selection. A true cabinet of curiosities. The overblown ambition of showing a whole century of art of such a vast continent could have no other result; the selection and the theme were ill defined, and the chosen items could only be assembled in the same place via the ethnological approach. It made one fact clear: what used to be classified as African Art had not yet found an adequate translation to the contemporary museum.

Vogel, like Pierre Gaudibert in his 1991 book Art Africain Contemporain, attempted to establish, if not a hierarchy, then at least a way of distinguishing between various African art forms. She did so using an empirical vocabulary, the limitations of which she was the first to acknowledge. However, two years previously, the discourse had taken a turn in another direction which, while not new, nonetheless caused waves that are still being felt today. Even though Jean-Hubert Martin’s 1989 exhibition Les Magiciens de la Terre at the Centre Georges Pompidou was not solely dedicated to Africa, it brought the debate into the public arena.

From the early ’90s, we could then discern two directions in the analysis of contemporary African productions: the ‘internationalists’, supported by Revue Noire, who rejected every form of triumphal exoticism and Africanism as embodied, for example, in the collection of the German Hans Bogadzke; and the ‘authentic’, the heritage of Les Magiciens de la Terre, most prominently represented by the collection of John Pigozzi.

These shows promoted the view that art could be anything as long it came from different countries and set up a kind of a political correctness based, once again, on ideas of Otherness. Meanwhile the ‘internationalists’ were trying to address African art using the same criteria applied to any other art practice, no matter where it came from. In spite of these radically diverging positions, African art had both sides to thank for having become a real topic of theoretical discourse, celebrated by numerous exhibitions and an ever increasing presence of African artists at big international events.

The lesson we’ve learned from the past 15 years and that will serve as our guiding thread, is that we must look at every contemporary African artist according to his or her own inspiration, regardless of any other context. Here, the context is understood as personal experience and shifts it away from any form of territoriality. Established methodologies are perhaps no longer suitable to solve the need for such sensitivities. We should resist any form of exoticism when selecting artists, otherwise the obligatory inclusion of a couple of Africans used to prove that the market has become truly global is in danger of becoming yet another curatorial trend. It is necessary to understand that it is no longer thinkable to accept the dictatorship of the market that not only sets up the prices, but also influences fashions in art and its inspiration. We must return to the artist, talk about the artist, analyse the work with all the tools at our disposal – none should be left out. There is today a dire need for transdisciplinarity. If during the ’80s discussions of contemporary African art were limited to a happy few, working almost exclusively in Europe (namely Paris and, to a lesser extent, London) and to a handful of ethnologists and anthropologists, the ’90s opened the way to a more idiosyncratic set of approaches. Its origins were no longer the primary criterion for the appreciation of a non-Western art work. The gaze became sharper. Contemporary art and museum curators joined with specialists. Using their position in the global culture game, they forced the discussion to tackle the work directly without necessarily focusing on origins.

The emerging curatorial approach, which substitutes a nuanced, individualised treatment of contemporary African art for an overwhelmingly territorial one, was/is the modest contribution of Africa Remix. It is also the aim of the newest initiative on the African continent, the Luanda Triennial in Angola. Scheduled to take place in spring 2006, it will attempt to bring the inscription of African art in the contemporary world to another level, while also trying to define its originality. The triennial will also attempt, on the one hand, to address the context in which all big international art events are constructed and, on the other hand, to offer new routes for reflection. Those routes could enable Africans to speak for themselves and to stop being the spectators of their own history, written, as it has been from the colonial times, by others.

Kainebi, Bisi & Mufu

From October 12 to November 10, CCA, the Centre for Contemporay Art, Lagos hosted Kainaebi Osahenye’s exhibition titled Trash-ing. A few days after the opening Mufu Onifade wrote in The Guardian newspaper a not very positive review. Bisi Silva took a few weeks and finally commented on Mufu’s views. I copy below both articles in case you missed them. I think they are worth reading.

In modern times, creativity goes Trash-ing

By Mufu Onifade, The Guardian, September 29, 2009

CREATIVITY is an expensive enterprise. It is invaluable and priceless. It glorifies its producers and executors. It also elevates its patrons and collectors. But not so with certain products of modern times: modernism has embraced all sorts of trash-able materials so much that the potency of art and creativity has been thoroughly wrestled. It is one of the banes of today’s artist who seems caught between the creed of aesthetics and mundane off-handed triviality. The road to real creativity is often hard and rough.

These and more are some of the posers raised by the art community after the opening ceremony of Osahenye Kainebi’s installation/exhibition titled Trash-ing and held at Bisi Silva’s Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos.

The show came with a flurry of murmuring which even took the shine away from the show. Kainebi, a seasoned painter who works and lives in Lagos and still maintains a studio in Auchi, has been on the art scene for close to eighteen years, especially with his first solo exhibition titled Tears in Our Time held in 1991 at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, Victoria Island, Lagos. He has since been very consistent with one solo exhibition after the other, without even ignoring continual appearances in group exhibitions. He is highly commended for using his creativity to contribute to aesthetic legacies that Nigeria can be proud of. Like every experimental artist, Kainebi grew through thick and thin of creativity and has now probably exhausted his purview.

At the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos where the opening ceremony of Trash-ing took place on Saturday, September 12, 2009, he transformed the cozy art centre into a depository of trash. More like a dust-bin, all objects (a collection of plastic bottles deliberately sliced into halves and some decorated in various tones of colour) were not arranged, but dumped to make a statement of trash. There were also dumped tubes of used pigments. The artist himself did not mince words in accentuating his thoughts and how he arrived at the dumping ground. He has run out of creative ideas, having painted all that was there to paint. He has exhausted his creativity in the purview of aesthetics and so, had to resort to something more degrading: the trash. In his explanation, the show was a kind of protest, a resonance of existing political and economic decay in Nigeria. In other words, he has used his art to chronicle the decay that Nigeria now parades among the comity of nations. Perhaps one should also add that Nigeria is stinking, although the stench was missing from the show.

If Kainebi and his promoter, Bisi Silva had thought their show was registered in the positive side of the viewers, they were mistaken. First and foremost, most people who came to see the show paid more attention to their inter-personal interactions rather than all objects of the show itself. Armed with plastic cups of assorted drinks and accompanying small chops, they hobnobbed, discussed in whispers and giggled aloud ireminiscent of a typical cocktail party. A few known artists in attendance would only turn the venue into an arena of convergence for like minds. They were all so subsumed by their subjects of conversation rather than being consumed by the objects of exhibition. They turned their backs on the works and faced their business of discussion as if everything depended on it. It is understandable. Nigeria is not used to these tenets of modern art, which, to a large extent, debases aesthetics and can be best described as an abuse of creativity.

Like the story of Ali Baba and the angel in the Oxford English book of yester years, the show attracted psychopathic comments as many were forced to disregard their innocence. Ali Baba told a gathering of grown-ups that there was an angel in a dark room. Anyone who sighted the angel was a good man. Whoever failed to see him was a bad one. Of course, everyone who entered the room claimed to have seen the angel. In truth, there was no angel at all, and that was an attestation to the gullibility of man. As for Kainebi’s Trash-ing, those who attended the show with smiles and positive comments were the one who understood and appreciated modern art. Those who think otherwise were backward and should go back to update themselves with happenings in the art of Europe. But this is Nigeria. A country that has produced classical artists who went through the training and had to battle with the seriousness embedded in formal art training and the primitivity of workshop or informal training. According to Oreoluwa Adedeji, a curator and consultant at the International Fine Art, Eagan, Minnesota, United States, “In the age of contemporary (modern) art, it seems as though the ideas of creating abstract and non-objective concepts, have given many artists an excuse to create works that are beautiful, but appear effortless and easily replicable. There is an anecdote about the ambivalence towards creativity and skill in contemporary art”.

Adedeji also told a story of relegation that has become the lot of modern art. Her words: “It is said that there was once an exclusive art auction in New York or London with many paintings auctioned to the highest bidders for hundreds of thousands of dollars. A time came for the last painting to be auctioned off. It was a colourful and simple abstract that mesmerized the ‘highly cultured’ audience. The painting was auctioned off for 1.2 million dollars. In the end, it was revealed that a monkey was the painter!”

That is the level of debasement to which world art has been dragged, but Nigeria, in spite of these modern trends, still maintains a respectable spot in the aspect of art and creativity. That probably accounts for the reason some Nigerian art collectors are more informed and knowledgeable than many artists. Those artists who are aware of these facts are also conscious of the quality of works they turn out.

Kainebi’s show was a combination of installation and exhibition. First, the works exhibited were quite unlike the Kainebi that we all knew. His illustrative prowess gave way to “non-objective concepts”, to borrow from the words of Adedeji. Although those colours applied to the sliced plastics are attractive due to their primary essence. They are applied raw and they stripped the objects of in-depth, analytical chromic infusion. As for the installation, it would be wrong for anyone to think that this aspect of art is alien to this part of the universe. In 1999, an installation workshop organized by the Goethe-Institut (German Cultural Centre), Lagos titled Swimming Calabashes was hosted by the Centre. Initiated by Emeka Udemba, a Nigerian artist based in Germany, the workshop attracted about 20 artists including Kunle Filani, Mike Omoighe, Toyin Alade, Deji Dania, Chuka Nnabuife, Mukaila Ayoade and others. At the workshop, Udemba made a mistake of referring to the workshop as the first in Nigeria. He was instantly corrected by participating artists.

In fact, Kunle Filani who migrated between the workshop and his work schedules at the Federal College of Education, Akoka, Lagos took the gathering of artists through a historical path to traditional African Art. In his argument, traditional Africa could boast of installation as part of its artistic and cultural history. Such objects that were used for ritual purposes could be found in shrines (like modern day galleries), crossroads (modern day outdoor erection) and many more. They served beyond aesthetic purposes and maintained a high level of spirituality for all partakers.

In summary, any form of art, whether in classical or modern term, must serve one of two functions: aesthetic or utilitarian. Any art that fails in any of these functions must be re-assessed. In the same vein, if installation is considered for any reason at all, the message must be graphically clear.

In defence of creativity, professionalism in arts writing

By Bisi Silva, The Guardian, October 20, 2009

ONE is compelled to react to Mufu Onifade’s article published in The Guardian of September 29, 2009 under the title In Modern Times, Creativity goes Trash-ing, considering the publicity that the show had generated.

In spite of Onifade’s comment, it is instructive to state that Trash-ing, a solo exhibition of mixed media work and painterly installations by acclaimed artist, Kainebi Osahenye had also highlighted some of the failings of Onifade’s arts writing.

However, it is believed that this rejoinder will further stimulate an informed discussion about painting specifically, exhibition presentation and ultimately the state of contemporary visual art practice in Nigeria.

While Onifade’s opinions of the exhibition are acceptable and valid within his own subjectivity, the irritating aspect of any review is when writers use art historical vocabulary with a total disregard for, or any minimal attempt at, contextualisation.

Onifade’s text is replete with confusions and sweeping generalisations. Besides, there is a plethora of inaccuracies. He talks about modernism without the briefest definition of what or which modernism he is referring to. Is he talking about European modernism? Is it early modernism of the mid 19th century that saw the rise of the avant – garde, when Eduoard Manet, with his painting, Le dejeuner sur l’herbe (1863), began to challenge the realistic representation of life in their work? Or is it the modernism that began with Picasso and the infamous Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) with its abstraction of the human figure and reference to African sculptural traditions? Or is it the modernism that saw the birth of the deconstruction of the art object with Marcel Duchamp’s readymade urinal, Fountain (1917)? Not only was Duchamp’s piece one of the most radical works of art of the early 20th century, it also changed the ways in which art was perceived and discussed as the precursor to conceptual art, and contemporary art.

Is Onifade conflating the ‘Modern’ with the ‘Contemporary’? And if so, to what end?

We can also consider Modernism on the homeground. Unlike what the canonisation of Euro-American modernism would want us to believe – that those outside of these ‘privileged’ geographical areas exist outside of history, out of time – the reverse is true. Africa and especially Nigeria was experiencing its own modernism.

A year before Picasso completed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, a pivotal work of 20th century European modernism ironically inspired by the African classical art, which he came across at the Trocadero Museum in Paris (now Le Musee de Quai Branly), Aina Onabolu completed a painting in oil of Lagos socialite, Mrs. Spencer Savage (1906). This, to date, remains the first oil painting apportioned not only to a Nigerian, but also to an African. In the late 40s and 50s, Nigeria’s own quintessential modern artist, Ben Enwonwu, moved away from the realistic portraiture eschewed by Onabolu towards combining African aesthetics and subject matter with European materials, a trend subsequently adopted and taken further in the 60s and 70s by the Zaria rebels such as Yusuf Grillo, Uche Okeke and Bruce Onobrakpeya. The stunning beauty of Enwonwu’s sculptural works, Anyanwu (1955) and Shango (1964) reflects this development.

These are a few examples of experimental, avant-garde practices, which continue today through the work of contemporary artists such as Osahenye and set the background to the rest of this text highlighting the writer’s ‘exhausted purview’.

It is also pertinent to clarify the programming policy of the hosting organisation. Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos has a curatorial and critical imperative that goes beyond hanging ‘things’ on a wall and putting red dots beside them. It aims at encouraging, supporting and providing a platform for the critical engagement with the changing dynamics of artistic practices outside an educational system that is relevant to 21st century realities. A system in which dead white men, of which Michaelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci sit unchallenged on the thrones, are repeatedly hailed – in Africa by Africans – as the hallmark by which all art must be judged. Unlike the ‘stench’ which is said to be missing from the exhibition, I say that the real ‘stench’ that exists is the stifling, putrid regurgitation of the same staid anachronistic paintings and sculptures that are churned out by the army of artisans in the name of art.

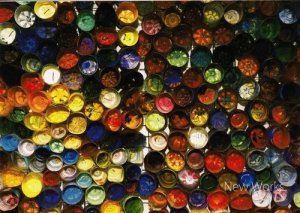

However, there are few areas in which the writer and I concur, especially as regards the extent of experimentation that has pushed Osahenye’s work to the forefront of contemporary artistic practice in Nigeria. That with each professional exhibition, his critical acknowledgement of the history of painting is manifest as well as the way his use of material has evolved, attests to his ability to leave behind his colleagues who take refuge in ‘churning out’ a repetitive signature style. His recent outing was a continuation of his experimentation with, and the use of, a myriad of objects and materials ranging from hair, paper, found objects and other ephemera to his current use of paper mache, bottles, cans, and oil paint tubes. What is interesting is that the more he changes, the more he stays the same, and the deeper his idea of painting becomes; yet the reviewer could not see that let alone engage with it. These were some of the characteristics that informed the curatorial decision to work on this project. It is rare for artists to create work that can be read on many levels – formal, aesthetic or contextual – revealing layers of stories, visuality and materiality. Oshayene’s Casualities 2009 installation is a case in point.

As I have written recently and I quote copiously: “Using appropriation as a tool, Osahenye’s most ambitious work to date is the ceiling to floor installation. On sighting the burnt cans near a garbage dump of a hotel in Auchi, Osahenye states that he ‘was instantly confronted with thoughts of war, cruelty, melancholy, pain, displacement, anguish and deformity and I started conceiving ways to install this large scale work to express the force and the power that I felt. Empty containers of bottled water, of Coca Cola, Pepsi Cola, Star beer, Malta Guinness, Heineken, Power Horse and other global brands of carbonated drinks representing the ‘detritus of urban existence’ are cut, coloured, sliced, squashed, squeezed, burnt has resulted in a large scale poetic installation. Osahenye employs this materiality to comment on the predatory nature of globalisation and the hegemony of consumerist behaviour at the expense of and to the detriment of the environment. In so doing, the result becomes a poetic tableau but also a scathing attack on the culture of Trash-ing.”

Apart from objecting to being called a ‘promoter’, a term more in keeping with a boxing event a la Don King, as a ‘real’ (many so called ‘curators’ abound) professional curator – one of the few with formal postgraduate training and qualification and local and international practice – I do take issue with his description of the presentation. Onifade’s statement reads: ‘like a dust-bin all objects (a collection of plastic bottles deliberately sliced into halves and some decorated in various tones of colour) were not arranged, but dumped to make a statement of trash.’

The 101 rule of curatorial practice is presentation. The way in which exhibitions are installed forms the cornerstone of any curatorial undertaking. However, with no visible curatorial antecedents in the complexity of installing such an exhibition, I am drawn to conclude that such intricacies are above his ‘experiential’ radar.

The presentation of the exhibition was a carefully thought-out and planned undertaking, which resulted in several conversations, studio and gallery visits between myself, the artist and the co-ordinator of the exhibition, Jude Anogwih, over a prolonged period. The placing of the works was not gratuitous but calculated and subsequently immaculately implemented. Casualities in all its deceptive manifestation as the most ‘unarranged’ work is actually the most meticulously arranged with the artist refusing to abrogate that responsibility to anyone else. He alone knows the way in which the work has to be placed for it to be meaningful. To say that the trash was dumped is not only a figment of the writer’s imagination, but demonstrates a lack of imagination.

This is not an Art History nor an Art writing lesson as neither are within my capacity. However, it is an indication that writing without appropriate references, or doing basic research, leads to misinformation. Trash-ing happens to be one of the few contextualised shows currently taking place that veers from the (p)sycophantic babble exhibition catalogues are so known for in this locality. Sylvester Ogbechie, professor of Art History at University of California, Santa Barbara wrote an insightful essay that tracks and contextualises the development and evolution of the artist’s work not only in regards to local and international artistic references and practices, but also through his use of materials and his subject matter. Philosopher/Art Critic Frank Ugiomoh of University of Port Harcourt also did a critique of the themes and issues in Osahenye’s work. Onifade’s review highlights an inability or unwillingness to engage with the work – references to the actual works are scant and derogatory, neither informing nor highlighting a coherent argument. That he was unable to rise to the discursive and aesthetic challenges that Osahenye’s work proffers and the context within which it has been developed and presented, reflects less on the artist but is an indictment of the level and the quality of the text.

Osahenye’s current exhibition also presents a different way to explore painting. Is there anything written somewhere that says that painting must be oil, acrylic, watercolour or pastel? That it must be figurative and literal? That what you see is what you get, leaving little or nothing to the viewer’s imagination. Such rule sank with the Titanic over a century ago. It is obvious that Onifade barely grasps with the idea or the history of the ‘dematerialisation’ of the art object. It is important to note that attempts by powerful critics such as American Clement Greenberg to prescribe the boundaries of art engendered a revolt by artists. And the resolve thereafter was that the emphasis should be on the idea behind the object, not on the object. Critics of visual art exhibitions like Onifade should take note.

Indeed, Osahenye’s work is a complex exhibition that needs to be read on many levels. That an art work or an exhibition allows such multiple readings is rare and real criticism should be about information, about thinking and about creating a platform for learning and debate.

Sylvester Ogbechie on Okwui Enwezor

At a recent conference in California about “The task of the curator” Sylvester Ogbechie, presented a paper titled “The Curator as Culture Broker: A Critique of the Curatorial Regime of Okwui Enwezor in the Discourse of Contemporary African Art.” It was nice of him to post it in its entirety on his personal blog (http://aachronym.blogspot.com). I think this is an excellent paper that should be read by all of us involved in one way or another in the production, dissemination, criticism, documentation or study of contemporary African art.

His views on Okwui Enwezor’s vision of contemporary African art are unambiguously critical. I am not in a position to offer a personal analysis of Enwezor’s curatorial activities. I have just finished reading his recent book (with Chika Okeke-Agulu) titled: “Contemporary African Art since 1980” and I was also able to listen to him at Bisi’s CCA last month, when he came to Lagos. Besides the usual references to his works as curator I do not know much of him yet.

The reading of ‘Contemporary African art since 1980” left in my mind a similar question to the one raised by “African Art now”, the book showing works from the Pigozzi collection. Though the criteria for selection of artworks and the critical framework in these two books is radically different, after reading them I was perplexed at the huge gap that exists between the “contemporary African Art” they portray and the “contemporary African (Nigerian) art” I see in Lagos. Is it that no contemporary art is produced in Lagos? Is it that those producing contemporary art in Lagos are hidden somewhere? Is it that only contemporary art that follows the hegemonic cultural canons from the West deserves global visibility? It would seem as if the continent itself is denied a central role in defining the identity of contemporary African art.

I am working on the project of a documentary book on contemporary Nigerian art in private collections in Lagos. The focus is on what Lagos collectors actually collect. I have already visited 29 collections and seen hundreds and hundreds of artworks produced and collected in Nigeria in the past 25 years. The immense majority of them would not find a place among the “primitive and exotic African stereotypes” preferred by Pigozzi or the post-modern art practices favoured by Enwezor and Okeke-Agulu in their book. There seems to be a problem here…

Though the focus of his paper is on curatorial practices, Ogbechi offers a convincing answer to my question. I hope it sparks a local debate on the issue of the identity of contemporary Nigeria Art. We need it if we want to move forward. My advice: read Ogbechie’s piece.