Ade is a sharp observer. Since he came back to Nigeria in 2005, after almost 25 years away, he has looked with empathy at this unique micro world that is Lagos. Finally, he has put into words and images a very personal portrait of the city. A few days ago, Ade mounted an exhibition titled “Icons of a metropolis”, accompanied by a book and an excellent web site. I was lucky to visit it twice.

First, he has identified twenty “icons”. He could have selected places, wares or objects, but he has focused, almost exclusively, on people. As he says: “Icons of a Metropolis” offers a non-judgmental look at 20 character archetypes – they are the ICONS. They are a creative force, a self-organizing and self-referential manifestation of the zenith of urban survival. The ICONs add colour, help to reflect our consciences, test our moral compasses and above all offer signals to the fragile points of the rapidly expanding ecosystem of a megacity. In their guise as evolutionary change agents they can be considered as the city planner’s guide or muse and as such are living mentors on the design requirements for mega cities”.

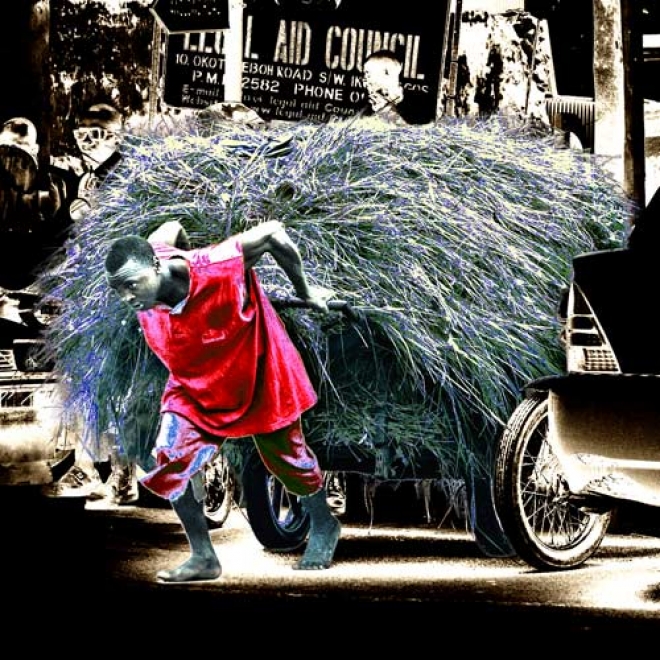

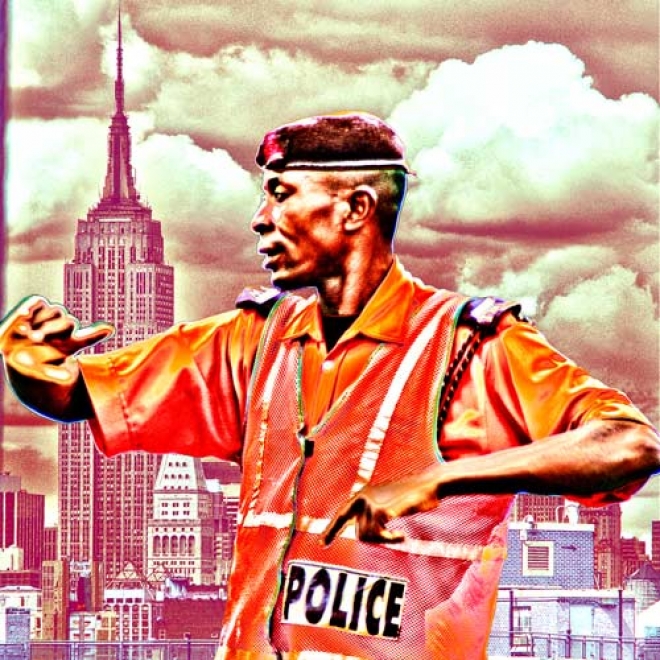

These are his twenty icons: the cart pusher, the beggar, the load carrier, the street hawker, the opportunist, the scrap man, the traffic policeman, the thirst quencher, the masquerade, the molue, the okada, the water peddler, the oil scavenger, the praise crier, the prayer warriors, the sand dredger, the displaced, the child bride, the challenger, the load carrier. We all know them, and we take them mostly for granted. Despite their ever-presence, they remain invisible, impersonal, but they make this city what it is. Individually, they dissolve in the urban fabric. Together, these icons “create” an urban fabric. They sustain the identity of this living assemblage of flesh, concrete, steel and blood. Ade, unveils that identity. Taken separately, each of these “icons” tells us a personal story. Together, they give the story of the metropolis.

Exit Ade, the social anthropologist. Enter Ade, the social archivist.

He has photographed these “icons” and made them visible. But documentary photography is only the raw matter for his work. His images are more philosophically ambitious than most of what we are accustomed to: Ajegunle, the markets, Makoko, the oil spills, etc. Referring to his artworks, he says: “(they) seek to tease the mind and invite viewers to engage, as a means of reflecting on their own lives and that of the society in which they live“. I think this is an apt observation.

Exit Ade the “documenter”, the archivist. Enter Ade, the artist-craftsman.

He does not present to the watcher an aseptic, realistic view of the icons. He has processed these raw images, manipulating colours and hues, contrast and saturation. Undoubtedly, Ade is extremely skilled in the use of image processing software, but he has not stopped here. The processing of the images enables Ade to give them a new life, conferring them a layer of disconnection from the realities they portray. Uncoupling from reality is accentuated by his use of solarization and colour shift processes. This is particularly successful in the photographs in which he plays with complementary colours: red on green, blue on yellow. In addition, by “detaching” the foreground from the background and playing with them in multiple combinations, he transforms a single image in a series of images.

Exit Ade, the computer craftsman. Enter Ade, the artist-creator.

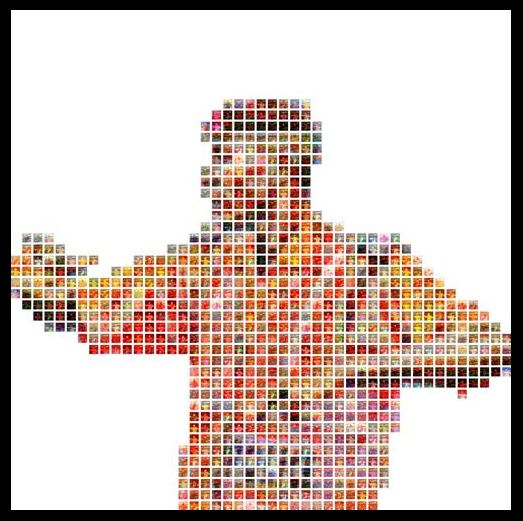

Producing the individually processed images is the beginning of a compositional work. The brief essay that accompanies the exhibition is succinctly titled: Repetition. This is the key word to his compositional strategy. In his words: “Repetition, whether it be visual, verbal, or cognitive creates conditions for new meaning by placing the old (that which is repeated) in a new context of an expanded range of considerations. Conceptually, repetition is powerful; it creates infinite combinations from finite elements – just as the ICONs create infinite possibilities from limited choices. He is passionate when he says that, through repetition, he would like his photographs to “go beyond a visual record of something we have experienced and become the source of a new experience. To become art”.

The end result is deceptive. What might have seemed the starting point, the photographs, is -in a way- the destination point. Does he go from reality to idea or from the idea to the concrete reality? Did the idea of the icons come before he went out to photograph them, or did he arrange them as icons once he came across them in his photography excursions through the city? Are we in front of a well structured (and manipulated) tableau of reality, or are we presented with the photographic embodiment of his “understanding” of the “icons of a metropolis”. What is first, the idea or the photograph? I am inclined to think that in Ade’s case it is definitely the former…

His web site for the exhibition can be seen at www.iconsofametropolis.com