In preparation for his coming exhibition at the National Museum, George Edozie will have on the 15 and 16 of March a private viewing of his recent works. It will take place at the Pan-African University, Victoria Island Campus.

I copy the few words I have writen as an introduction to the exhibition.

Expression of a journey

George Edozie has titled this exhibition of his recent works “Expression of a journey”, and this label is only partially apt. Those of us who have followed his growth as an artist know that expression is a recurrent word in his vocabulary and a defining concept in his self-understanding as an artist. But he is not, he can’t be, an expressionist in the way Herwarth Walden used this term for the first time in 1911. Much less is he in line with the neo-expressionist painters in Germany, Italy and USA in the late 1970’s: Baselitz, Clemente, Kiefer, Schnabel.

In a loose way, he is, and we are all “expressionists”. We express ourselves through all our actions: when we choose a pair of shoes or when we decide what of telephone handset to buy… In an artwork, the themes, colours, techniques and materials, what is present and what is absent, the shouts and the silences, always tell us something about the artist, and about the time and cultural milieu in which he or she lives. Whoever has stayed for a few minutes in front of the Guernica knows how powerfully Picasso expresses his anger and his pain. Anybody in front of the Pietá, is touched by Michelangelo’s expression of tenderness and grief.

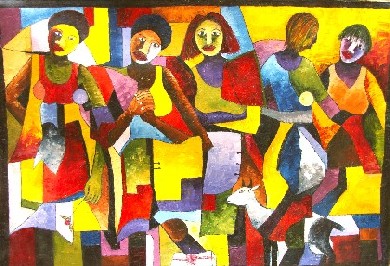

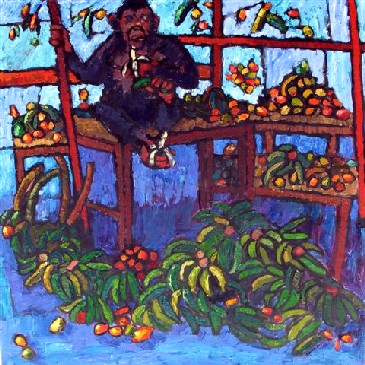

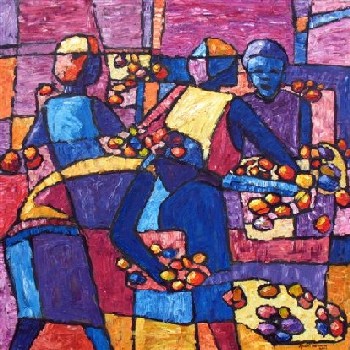

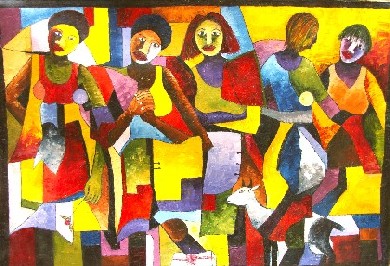

No, George Edozie is not an expressionist, but he shares a good number of the formal characteristics of the “fauvist” and “post-impressionist” painters at the turn of the 20th century: Cezanne, Matisse, Gauguin, Van Gogh. In different ways, these artists went beyond the manner in which impressionism focused on reproducing the impression caused by the physical world. For the “fauves”, what mattered were the subjective, personal emotions provoked in the artist and their expression through strong, colourful, vibrant use of formal elements. They were not trying to reproduce the impression brought about by the immediate physical reality, but to express the artist’s inner world and his or her reaction to the external one. In common with them, Edozie’s works show some recurrent features: (1) use of bright, primary colours, (2) use of the impasto technique, and (3) use of simplified forms.

“I exaggerate the fair colour of the hair, I take orange, chrome, lemon colour and behind the head I do not paint the trivial wall of the room but the Infinite. I make a simple background out of the most intense and richest blue the palette will yield. The blond luminous head stands out against this strong blue background mysteriously like a star in the azure. Alas, my dear friend, the public will see nothing but caricature in this exaggeration, but does that matter to us?” These clear words of Van Gogh, said a century ago, have been learnt well by George Edozie. One only has to look at any of his numerous “tilting heads”.

Edozie does not just stand in front of a person or a still life and paints what he sees. He paints what he feels. What pains, gladdens or worries him… Like the Yoruba woodcarver, he does not try to reproduce. He paints what he knows, not what he sees. That is why his faces are always “the face”; made of exactly the same elements repeated over and over again throughout the years: two oblong white eyes with a circular black iris, sensuous lips (always closed, always red, always the same…), no ears, long, tilted neck, black contour lines, flat –perspectiveless, monochrome- background…

In this, he follows the famous Van Gogh dictum: “Instead of trying to render what I see before me, I use colour in a completely arbitrary way to express myself powerfully”. In his works, there is neither an imitation of reality nor a quest for the “creation” of perfect beauty. For him, expression rules over mastery and he tries to achieve it mainly through the use of colour and texture. In the works shown in this exhibition, he generally disregards the tonal graduation of traditional painting and gives autonomy to colour (mostly, unmixed) and brushstrokes. That is why some of these works might seem strident and brash at first sight. Lately, he has started introducing “collages” and pastel colours and this is softening considerably the strength of his paintings.

Edozie is not an “expressionist” because -though there are some formal similarities- the mood, the ethos, are different. The members of the pioneer expressionist group Die Brücke (The Bridge) —Kirchner, Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluff and Bleyl—were obsessed with dark images of anxiety, angst and alienation. George Edozie is not, though few of his works are cheerful and there is no much joie-de-vivre in them. In the best ones, there is restraint, permanence and calm.

Perhaps because he studied at Benin, and not at Nsukka, Zaria, Auchi or Ife, George Edozie is a loner among Nigerian contemporary artists. Unlike in the case of most of Nsukka or Ife artists, tradition does not play a central role in his works. He is not enriched (or burdened?) by the past, but he is also able to go deeper than the shallow formalism of many the Auchi artists.

Because he does not believe in art for art’s sake, there is a “narrative” behind each painting, an engagement with people and society, an active look at persons, situations and the dynamics of social groups. This is, in my opinion, his greatest strength and what provides significance and potency to these singular works.