Yesterday, Olumide Onadipe opened at Temple Muse an exhibition of his recent works titled ¨Connecting the dots¨ and organized by SMO Contemporary.

Olumide continues evolving and maturing an artist. Though he started his professional career producing realistic paintings, in recent years, he has experimented with plastics and other media to produce sculptural pieces of profound quality, meaning and beauty. For those of us who have followed him for more than a decade, his new works do not present themselves as a surprise or a rupture, but as an evolution and deepening of ideas and formal solutions that are gradually developing as Olumide grows as an artist. He is a versatile artist comfortable with different types of media, so in “Connecting the dots”, Olumide, presents two distinct bodies of work: paintings and sculptures.

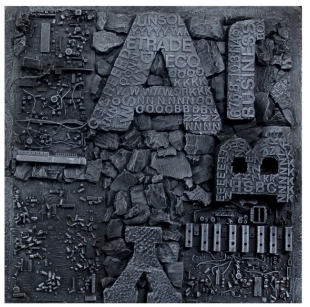

He initiated his artistic practice as a two-dimensional painter. Then, around 2008, he started rendering abstracted faces and figures masked with vegetation. Ten years later, in his paintings, leafs continue being a recurrent compositional element, but his vocabulary has expanded and the works have acquired a greater complexity and a deeper meaning. Nevertheless, the present exhibition shows that while his roots are still in painting, and some of the sculptural works retain a distinct pictorial character. His artistic identity is increasingly defined by his experimentation with plastics, paper, newsprint, cement bags, and other materials.

He initiated his artistic practice as a two-dimensional painter. Then, around 2008, he started rendering abstracted faces and figures masked with vegetation. Ten years later, in his paintings, leafs continue being a recurrent compositional element, but his vocabulary has expanded and the works have acquired a greater complexity and a deeper meaning. Nevertheless, the present exhibition shows that while his roots are still in painting, and some of the sculptural works retain a distinct pictorial character. His artistic identity is increasingly defined by his experimentation with plastics, paper, newsprint, cement bags, and other materials.

Olumide has always acknowledged the great impact Kainebi Osahenye’s exhibition titled “Trashing” had on him in 2009. It was a discovery. As he says speaking about that exhibition: “It switched on my inner light and became a guiding compass to what now characterized my artistic pursuit.” But, while his first works using melted plastics were tentative and, perhaps a little bit uncertain, the recent ones are much more assertive. Olumide is finding an aesthetic vocabulary and a formal language that allow him work with ideas and meanings in a much more forceful way.

Olumide has always acknowledged the great impact Kainebi Osahenye’s exhibition titled “Trashing” had on him in 2009. It was a discovery. As he says speaking about that exhibition: “It switched on my inner light and became a guiding compass to what now characterized my artistic pursuit.” But, while his first works using melted plastics were tentative and, perhaps a little bit uncertain, the recent ones are much more assertive. Olumide is finding an aesthetic vocabulary and a formal language that allow him work with ideas and meanings in a much more forceful way.

Gradually, Olumide is mastering the primary elements of sculptural artworks: volume and line, weight and mass, shape and texture, solidity and flimsiness, emptiness and fill, roughness and smoothness, order and improvisation, colour and form. But, perhaps, the defining feature of these sculptural works is the fact that they are generally made of countless small units –each one similar, but each one different from the others- put together into a single piece. In this, he is not far from the work of some prominent contemporary artists in Nigeria: El Anatsui, Olu Amoda, Kainebi Osahenye, Eva Obodo.

Gradually, Olumide is mastering the primary elements of sculptural artworks: volume and line, weight and mass, shape and texture, solidity and flimsiness, emptiness and fill, roughness and smoothness, order and improvisation, colour and form. But, perhaps, the defining feature of these sculptural works is the fact that they are generally made of countless small units –each one similar, but each one different from the others- put together into a single piece. In this, he is not far from the work of some prominent contemporary artists in Nigeria: El Anatsui, Olu Amoda, Kainebi Osahenye, Eva Obodo.

When Olumide refers to his sculptural works he presents a narrative with allusions to socio-political issues. But these physical commentaries on events, social customs and malaises that affect Nigerian society are rarely explicit. In most cases, they vaguely suggest something through their form. In a few others, it is only the title of the work that opens the door to possible interpretations and readings by the viewer. Olumide is well aware of the difficulty of embedding meaning into a non-representational sculptural form. Nevertheless, since he started painting, he has been very much concerned about meaning and communication. The impenetrability and inherent muteness of matter are a challenge he takes head on with the hope that his works will, eventually, be able to relate, to communicate to both, the body and the mind of the spectator.

When Olumide refers to his sculptural works he presents a narrative with allusions to socio-political issues. But these physical commentaries on events, social customs and malaises that affect Nigerian society are rarely explicit. In most cases, they vaguely suggest something through their form. In a few others, it is only the title of the work that opens the door to possible interpretations and readings by the viewer. Olumide is well aware of the difficulty of embedding meaning into a non-representational sculptural form. Nevertheless, since he started painting, he has been very much concerned about meaning and communication. The impenetrability and inherent muteness of matter are a challenge he takes head on with the hope that his works will, eventually, be able to relate, to communicate to both, the body and the mind of the spectator.

Generally, he does not work with untouched materials and there is heavy labour involved in the process of producing each of his sculptural works. Through physical and mechanical processes of breaking, melting, rolling, folding, wrapping, tying, welding and aggregating, the common materials retrieved and used by Olumide acquire a new life in his works.

Generally, he does not work with untouched materials and there is heavy labour involved in the process of producing each of his sculptural works. Through physical and mechanical processes of breaking, melting, rolling, folding, wrapping, tying, welding and aggregating, the common materials retrieved and used by Olumide acquire a new life in his works.

In his work titled “Pyramid scheme” Olumide takes his aim at the fraudulent financial schemes, unfortunately, so common in the country in past years, taking money from the poor to give it to the rich schemers. The works in his “leg series” are about the movement of ideas, people and objects into and from the African continent. About those who came –and continue coming- and about those who left the continent and took with them part of it. The “legs”, in Olumide’s recent works are a powerful metaphor for change, for transitions and trade.

The physicality of these pieces is such that the first response to the encounter with them cannot but be intuitive –perhaps, I should say, instinctive. Then, there might be a complex process of perception, assimilation and rationalization of the narrative that permeates these works or, perhaps, the work may remain silent, incapable of conveying what the information we receive is supposed to tell us. In either case, the first response is almost instinctive. With the works of many artists, it is possible to remain indifferent, untouched and removed. In the most successful works in this exhibition, this is not generally the case. They talk to us forcefully.

The physicality of these pieces is such that the first response to the encounter with them cannot but be intuitive –perhaps, I should say, instinctive. Then, there might be a complex process of perception, assimilation and rationalization of the narrative that permeates these works or, perhaps, the work may remain silent, incapable of conveying what the information we receive is supposed to tell us. In either case, the first response is almost instinctive. With the works of many artists, it is possible to remain indifferent, untouched and removed. In the most successful works in this exhibition, this is not generally the case. They talk to us forcefully.

Consistently, Olumide Onadipe is building a substantial body of work with a well-defined artistic identity easily recognizable in the growing panorama of contemporary sculpture in Nigeria. “Connecting the dots” is another step forward. I hope not to miss the next one.

Consistently, Olumide Onadipe is building a substantial body of work with a well-defined artistic identity easily recognizable in the growing panorama of contemporary sculpture in Nigeria. “Connecting the dots” is another step forward. I hope not to miss the next one.

Jess Castellote